Vietnam’s draconian fines for runaway overseas workers point at TPP dilemma. US Secretary of State John Kerry during his current Far East swing is certain to raise human rights concerns with his Vietnamese hosts, who are feverishly working to make Vietnam worthy of Trans-Pacific Partnership accession.

It is doubtful, however, that the Vietnamese government’s Decree No. 95/2013/ND-CP will be anywhere near Kerry’s agenda. In effect since October and to be enforced after a three-month grace period, the decree will force Vietnamese overseas workers to face fines of 80 million to 100 million Vietnamese dong (US$3,800 and US$4,700) if they abandon their foreign employers, as vast numbers of them do to escape predatory brokers at the end of the term of their labor agreements.

According to Taiwan’s Council of Labor Affairs, the number of “uncaptured missing” Vietnamese reached 19,878 at the end of October, reflecting a hefty 31.2 percent annual increase, apparently hiding from the massive fines.

Simple math makes readily graspable how much a human rights issue Decree No. 95 is – given that the average wage in Vietnam is around 3.2 million dong (US$150) a month, someone working in the country would have to toil without paying for food and water for more than two years to pay up.

“As labor export is an important part of Vietnam’s economic development strategy, the harsher punishment on runaway guest workers was likely mainly driven by international pressure,” Zheng Yu, a University of Connecticut political scientist with interest in Vietnam, told Asia Sentinel.

“In August 2012, South Korea suspended the bilateral agreement on employing Vietnamese guest workers due to a large number of runaway Vietnamese workers who illegally overstayed. Although this suspension was recently lifted, it has cost more than 10,000 Vietnamese guest workers’ jobs, which was a big blow to Vietnam’s labor export sector.

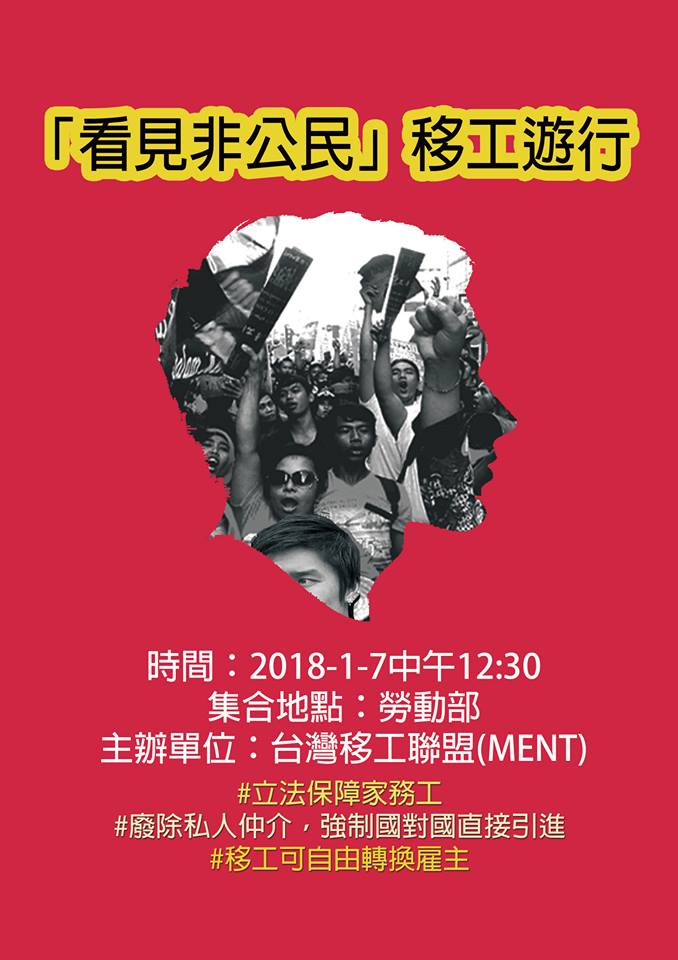

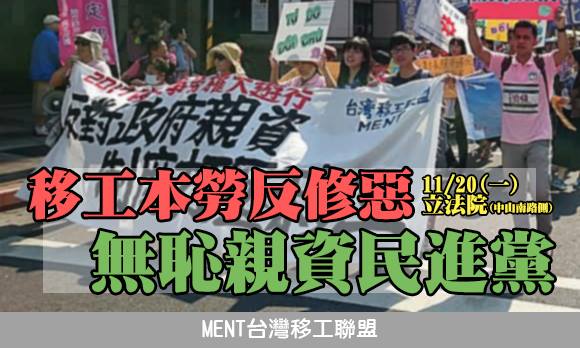

”According to Vietnam’s official statistics, 500,000 Vietnamese workers are abroad in more than 40 countries. Each year, about 80,000 workers are sent abroad with Taiwan, Malaysia, South Korea and Japan being the major destinations. In Taiwan, where NGOs in mid-December launched a demonstration against Decree 95 in front of Vietnam’s de facto embassy, there are currently 122,000 Vietnamese workers out of a total foreign worker population of 480,000, with about 20 percent of them employed in metal production and human health/ social work.

NGOs are not surprised that nearly 20,000 Vietnamese have absconded.

“Vietnamese law sets the maximum broker fee at US$4,500 and requires that the worker sign the contract with the broker in the presence of the Vietnamese police,” noted Peter Nguyen Van Hung, Taiwan-based executive director of the Vietnamese Migrant Workers and Brides Office. “However, on the day of departure the broker usually forces the worker to sign another agreement stipulating a total fee of US$6,500 to US$7,500.”

A pullout is not an option for the workers at that late stage in the immigration process, Hung continued, because they have typically earlier deposited the ownership certificates for their family farm or house to get a loan from the bank in order to pay for broker, passport, airfare, health check and so forth.

“They have no choice since they would otherwise lose all that money,” he said. According to Hung, what then often follows is just as appalling. After the worker’s arrival in the host country, the local employer might not be willing to pay what the broker has promised, and there are abundant cases of abuse of the workers by the employers. Then there is the black market for runaway workers driven mainly by ample demand in construction, farming and manufacturing, with the word of mouth pointing at the only plausible way out of the worker’s desperate situation. “

The only way to deal with it is to run away. This decision often makes the workers subject to secondary abuse,” Hung said. He predicts that the number of Vietnamese runaways will initially decrease slightly due to Decree 95 but it will then return to an upward path because the core problem is only dealt with at the surface. According to Hung, there are indications that if that happens, Vietnam police are ready to arrest absconders’ relatives back home in Vietnam and keep them in custody until the fines are paid.

Hung agrees that Hanoi’s main motive is to make a good impression on international authorities, in Taiwan’s case presumably to achieve a lift of a decade-long import freeze on Vietnamese care-givers.

“But if the Taiwanese government knows about Decree 95 and doesn’t do anything about it, it is complicit in human exploitation and involuntary servitude. Also, the harsh punishment will make people not voluntarily turn themselves in, causing Taiwan’s society a problem,” he said.

Still, Hung and others acknowledge that the Taiwanese side has come quite a long way in the past few years. Traditionally, the approach of choice has been mediagenic manhunts, such as one in the autumn of 2004 when Taiwan police in cooperation with the very Vietnamese brokers that are the main cause of the workers’ misery rounded up 500 in one month. The 100-odd brokerage personnel who were flown in from Vietnam for the job simply traced the absconders’ remittances and then presumably threatened the relatives in rural Vietnam in order to make them come up with information on the absconders’ whereabouts in Taiwan. Replying to Asia Sentinel’s query, the labor affairs council said Vietnamese authorities haven’t informed Taiwan on Decree 95. The agency also denied speculation that Taiwan was an overseas labor destination that had pressured Hanoi to craft harsher penalties in the first place, arguing that the council has instead long recommended cutting onerous broker fees. The agency furthermore said it is actively assisting absconders who have been voluntarily turning themselves in during the three-month grace period, and moreover pointed out that it “has built a complete protection system for foreign workers which applies from prior to arrival to until departure.” And, aiming at making brokers once and for all unnecessary a “direct hiring joint service center” has been set up, among other measures.

The foreign worker issue is so complicated that even well-intended policies easily become counterproductive, however, Hung said, adding that in a perfect world, overseas employers would pay a labor broker to recruit suitable men and women.

“But the attempt to circumvent the brokers has created a perverse situation: I have heard that the broker now pays the employer with the money he has squeezed out of the worker,” Hung said.

Meanwhile, South Korea has only reopened its doors for the import of Vietnamese workers after a pilot program making mandatory a refundable deposit of US$4,800 by each worker was implemented by Hanoi. Needless to say, together with Decree 95, the pilot program would make the financial loss truly astronomic for absconders.

In the best of worlds, Vietnam would assure Kerry during his visit that the government will meet commitments on labor rights under the TPP, which always has been one of the core issues in the US’s free-trade agreement negotiations.

According to the University of Connecticut’s Zheng, Vietnam probably will negotiate a “phase-in” period to reform its labor laws and demonstrate its respect to basic workers’ rights, particularly in export industries.

“The irony is that harsh punishment on runaway workers is a step toward the direction of improving workers’ basic rights as it sets a higher standard for labor export,” Zheng said. “But on the other hand it has raised concerns about the violation of human rights for illegal workers. It is a dilemma for the Vietnamese government.”